Fall/Winter 2025

Shape Shifting AFTER KATRINA

Bobbie Green on surviving extreme weather and practicing collective care

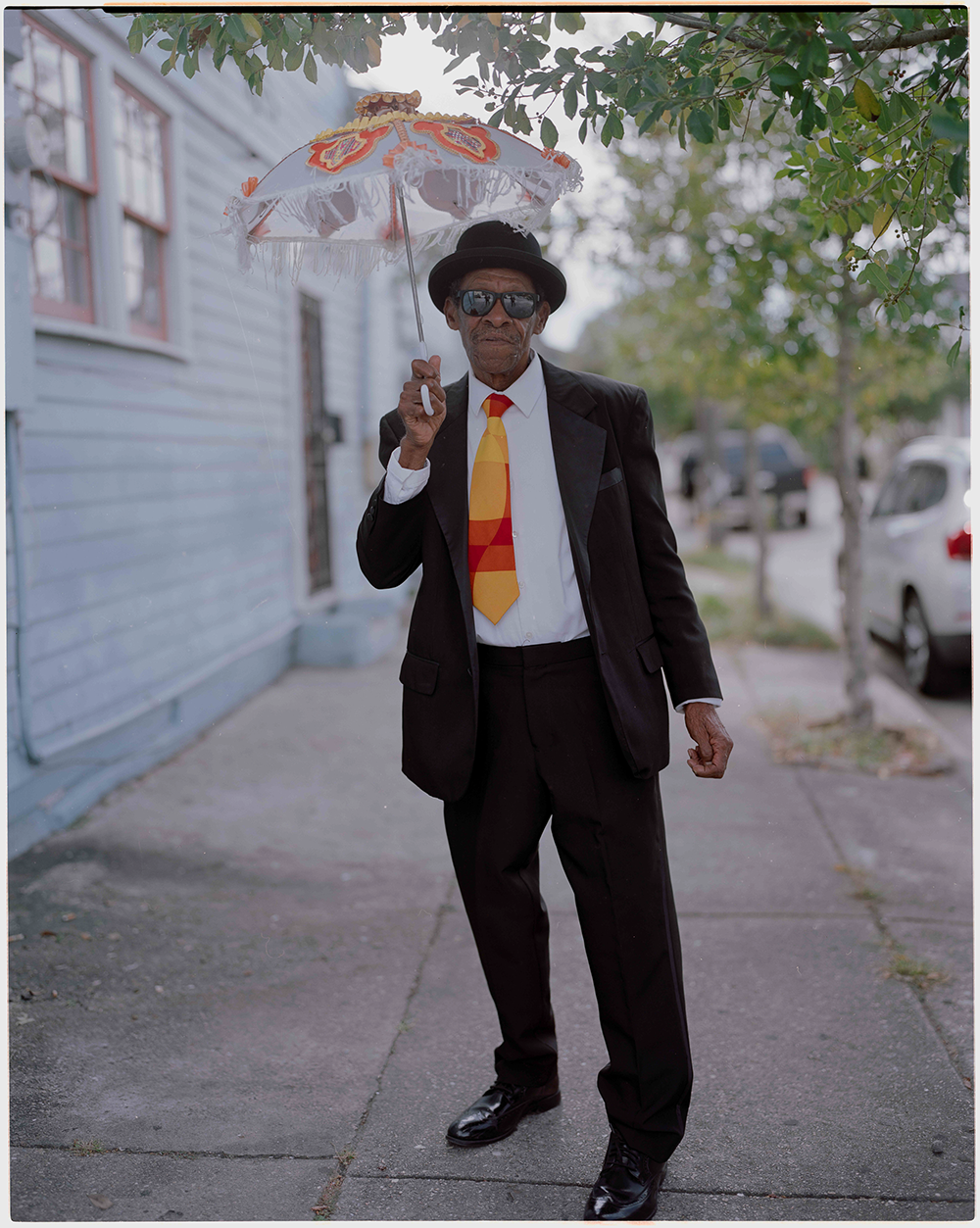

Almonaster Ave, St. Roch, New Orleans. Cowboys gather under cypress trees at the 9 Times second line. Photography by Brandon Holland.

As the New Orleans HUB leader for Black Girl Environmentalist (BGE), Bobbie Green is a conduit for community connection. She’s passionate about creating programming that inspires Black women, girls and gender expansive folks to find their role within an intersectional climate movement.

Bobbie is also a ‘Katrina baby’ whose family was displaced for 10 months after Hurricane Katrina. That experience shaped how she sees the world and ultimately set her on a path to becoming an organizer and advocate for environmental justice and community. Over the years, she’s built a career in communications, working with mission-driven organizations to tell stories that make complex environmental issues feel human and accessible, rooted in the voices and lived experiences of the communities most affected.

Outside of her work with BGE, Bobbie is using her talents to deepen her impact in the digital space, focusing on how storytelling can move people to action. She’s exploring new ways to spotlight local organizations doing environmental justice work, share timely climate news, and uplift community events that deserve more attention online.

In this personal narrative, Bobbie shares more on the impacts of Katrina, the necessity of meeting people where they are, and the value of cultural reclamation.

ON SURVIVING EXTREME WEATHER & SUPPORTING MENTAL HEALTH

Being a nine-year-old in the throes of a major storm like Hurricane Katrina was life-altering. Katrina is the cataclysmic extreme weather event. It was the first disaster where we were able to really expose environmental injustice, and it was also my very first experience living through extreme weather.

My family and I were displaced for 10 months after Hurricane Katrina. That's 10 months in a whole other city, state. That’s 10 months being referred to as refugees when just a few days before evacuation, I had a home, a community, that was since ripped away. I had to shape-shift into a new life for nearly a year, and then coming back to a home that was no longer what it used to be was very hard.

“I had to shape-shift into a new life for nearly a year, and then coming back to a home that was no longer what it used to be was very hard.”

Despite the severity of the storm, so many of us who were young during Katrina didn’t understand the weight of the hurricane, and what it would mean for our lives. I know for myself that I had to compartmentalize a lot of the impacts of the displacement, and also a lot of the feelings that I had because of it: like resentment that the storm happened, and how it completely restructured the course of our lives. I don't have many memories of New Orleans before Katrina because I was so young, but my older siblings and cousins and extended family members do. Generations of New Orleaneans remember a city that’s very different from my understanding, and that generational divide can be difficult to bridge.

I hadn’t really reflected on the scope of that loss until I came across the Katrina Babies documentary from the New Orleans director Edward Buckles, Jr.. A big part of that film focused on the mental health issues that New Orleans youth had to deal with because of the long-term impact of Katrina on their communities. So much was taken away from me and others my age, in part because there was no care given to the youth at that time. We leaned on each other a lot, but we didn't have the institutional support that we should have had: our mental health was just not a priority. There was no therapy, support counseling, check-ins. There were no resources from our local government or the schools to help us through our trauma. Some of us had seen worse devastation than others up close, and we just were not properly cared for before, during and after the storm.

“There was no therapy, support counseling, check-ins. There were no resources from our local government or the schools to help us through our trauma.”

Photography by Brandon Holland.

ON COMMUNITY CARE & ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY

My own advocacy working in the environmental justice space has really been shaped by that experience. Seeing families ripped apart, loved ones lost, and homes devastated all because our government failed us by not prioritizing Black and Brown people was deeply impactful. It’s why working as an environmental justice steward, and being knowledgeable around disaster and environmental issues impacting my community, is so near and dear to me. I want to be the advocate I didn’t have when I was growing up.

“Our health is directly tied to our natural environment, so we need to be kind to ourselves and to our environment.”

Today I am a community organizer with Black Girl Environmentalist, a national organization dedicated to addressing the pathway and retention issue in the climate movement for Black women, girls and gender expansive folks. As the HUB lead for New Orleans, a lot of our programming centers around environmental education, community wellness, and creating the space to make the connection between environmental injustice and public health. Our health is directly tied to our natural environment, so we need to be kind to ourselves and to our environment.

One of the things that I prioritize for the New Orleans HUB is really being able to meet folks wherever they are in their climate journey. We have people who have experience working in the climate or environmental sector, and we also have people who work in the health or hospitality industry. As a HUB lead, I am happy that I am able to be a collaborator. I see myself as a conduit for connecting folks to educational resources, as well as to other individuals who might help them grow. I’m also here to help people pivot careers if they want to make a move into the green sector. Even though so much of the federal funding has been rolled back for clean energy and conservation-related policies, green jobs are blooming, and there are still opportunities to get involved, even if it’s as a volunteer.

SPOTLIGHT ON LOCAL ORGANIZATIONS

As part of my work with Black Girl Environmentalist, I partner with local organizations that are focused on disaster recovery solutions rooted in our communities and our culture. We've done workshops and environmental impact days with the Sankofa Wetland Park & Nature Trail, for example, to support them with their work. The park comprises 40 acres of wetlands in the Lower Ninth Ward, and is maintained by organizers who are committed to revitalizing one of the neighborhoods most affected by Katrina. In addition to their wetlands restoration work, Sankofa has built a community garden and grocery store. They are a beautiful model of putting community-led solutions into practice.

Out in New Orleans east- past the levee and over the train tracks lies Lincoln Beach. During the Jim Crow era, it served as New Orleans’ black swimming area, and while it was officially closed in 1965, there has been a recent communal grassroots effort to restore and care for the beach. As a result, Lincoln Beach has once again become an oasis for New Orleans’ residents, particularly people of color. Photography by Brandon Holland.

We have also partnered with programs such as the New Orleans Water Collaborative during the first New Orleans Water Week, a vibrant, week-long celebration that honors the vital role water plays in shaping the culture and future of New Orleans and its surrounding coastal communities. More recently, we facilitated an event with Sisters in Public Health where we brought women together to talk about how to prioritize mental wellness and physical wellness in this work. I’ve been personally inspired as well by the work of Taproot Earth, an organization fighting for Black Liberation and environmental justice in the Gulf South. I participated in their Black Climate Leadership Summit in Puerto Rico. More than 20 different countries in the diaspora were represented, and it was a profoundly transformative experience.

This year, I had the opportunity to begin working with a new organization called Extreme Weather Survivors (EWS) that really centers the experiences of community members who have navigated traumatizing disasters. As Communications Manager for EWS, I help to amplify stories of survivors impacted by extreme weather events. A core part of our work is providing trauma-informed peer support for survivors of hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and other extreme weather events, along with advocacy opportunities for those ready to speak out and push for timely, co-created solutions and policies that protect our communities and future generations. One of the unique things I've seen with this organization is how powerful it is to have a space where people from across political lines and generations are able to swap resources, share experiences, and support each other.

ON CULTURAL PRESERVATION & CO-CREATED SOLUTIONS

Many of the organizations I mentioned reflect New Orleans’ culture of care. And anybody who has either heard of, been to or experienced New Orleans—before Katrina especially—thinks of culture. The music, the food, the smells, the people, the hospitality, the Mississippi River, the bayous—it’s just amazing right?

“Rebuilding will require us to both recover the essence of New Orleans that was lost to the storm, and carve a new path that reflects the times we are in.”

A small second line passes by Backstreet Cultural Museum in the historical black neighborhood of Tremé, before making a stop at Tubafats Square. Photography by Brandon Holland.

But there were so many layers of culture that were stripped away from New Orleans when that storm hit. Speaking from my family’s experience, they grew up in an entirely different New Orleans. We’ve had to have many real and raw conversations about how things have changed. In the last 20 years, for example, we’ve witnessed waves of gentrification, and the impact of economic, social, and systemic disinvestment on many of the poor, Black, and Brown neighborhoods most impacted by Katrina. People have been priced out of their community, and this has threatened our ability in turn to fight for a just recovery. When I envision the impact of Katrina, I see how it lives in our recovery, our streets, our homes. I see it in how we are continuing to fight, 20 years later, for infrastructure and revitalization initiatives that truly support our needs.

Rebuilding will require us to both recover the essence of New Orleans that was lost to the storm, and carve a new path that reflects the times we are in. In my day-to-day, I'm very service-driven. I always care about the person. We all deserve equitable access to clean water, clean air and opportunities to enjoy nature without degradation and destruction.

Above all, we deserve to have our stories heard. Traditionally, a lot of us working in the environmental justice space are unseen, especially women, Black women, Indigenous individuals, Brown people. We do our best to take care of each other, and to see each other. This is why I am committed, as a younger organizer, to continuing to sponge up resources from climate leaders that look like me.

“Traditionally, a lot of us working in the environmental justice space are unseen, especially women, Black women, Indigenous individuals, Brown people. We do our best to take care of each other, and to see each other. ”

It’s also why I am committed to continuing to create spaces and campaigns that facilitate deeper connection. Because when I think about what reclamation for New Orleans looks like, I think it's about community engagement. I think it’s about uplifting community-driven solutions and working in partnership with our local government and city officials to put our visions for collective resilience and a just recovery into action.

Co-created solutions are the answer. We need to bring community members and local leaders to the table to co-create solutions. As we build the “new” New Orleans, now is the time for everybody to be hands-on so we can continue to both recover traditions and chart a vibrant future for our community.

Bobbie Green is the New Orleans Hub Lead for Black Girl Environmentalist, joining the role with a background in strategic communications and community engagement. She is passionate about expanding access to the outdoors, cultivating environmental leadership, and creating inclusive pathways for Black women and gender-expansive individuals in the climate movement. Bobbie has worked with mission-driven organizations to develop and execute storytelling, advocacy, and marketing strategies that inspire action and foster belonging. Outside of her work with Black Girl Environmentalist, she enjoys exploring local green spaces, traveling, and connecting with her community.

Peace & Riot is a nonprofit publication and free to read.

We believe access to movement-rooted storytelling should remain open and accessible.

But sustaining this publication requires sustained funding.

If you value independent storytelling that uplifts frontline voices, honors lived experience, and strengthens cultural resistance, please consider supporting our work with a tax-deductible donation.

Your contribution helps sustain the journalists, editors, artists, and storytellers who make this digital zine possible — and ensures Peace & Riot remains a platform for connection, truth, and creative expression.

Support Peace & Riot today.